Rick’s Flicks continues its serialization of Harry Richards’ book THE JUDY WATCH, but first . . .

A TELEVISION JACOB

Rick’s Flicks, as policy, does not review or discuss television dramas or films made for television, but JACOB cries out for a response.*

One would not think that the telling of the Biblical patriarch’s story could ever be bland.

But . . .

Matthew Modine’s Jacob bears no charisma. Actually, it all right if Jacob appears ordinary. He was Yahweh’s darling and would succeed — no matter what. But there needs to be some kind of specialness. And the Bible’s great lover should look special.

Lara Flynn Boyle is attractive and talented but does not have the makings of the most beautiful woman in the Hebrew Bible — at least in the eyes of Jacob. Most surprising of all, Irene Papas shows no strength or force as manipulative matriarch Rebecca. She is a whining nag. With Leah as the most likeable character, there IS something wrong with this picture.

*Acknowledgment to Margaret Mitchell for my borrowed paraphrase.

Jacob Turner Pictures a Lube production teleplay by Lionel Chetwynd

* * * * * * * * * * *

Harry Richards is a free lance writer out of Missoula, Montana. He has spent much of his life observing, studying and analyzing the work of Judy Garland. There are now fifty plus books about Judy Garland, but Richards believes that his is the first devoted to her live concert performances. Richards enjoys being a father and grandfather. He likes flowers, reading and viewing films.

JUDY THREE

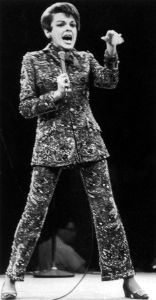

The Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles was a clumsy old barn showing its age. The proscenium arch embraced a dramatically wide area. The evening I chose from the five-night engagement proved an unusual and uneven concert.

Friend John L. was unable to accompany me and do his usual generous driving. Bob, a Judy fan — though not in my hysteric league — drove us there. I had been clutching my third row center ticket for weeks, but Bob bought a balcony seat that night twenty minutes before the show. This would be the first live performance he had seen by the great Lady as he called her.

My luck, or lack of it, as to audience members near me continued. There were scattered vacant seats downstairs though the balconies were full. In my third orchestra row, believe it or not, I had no one on either side of me. But two loud, crass women took seats behind me just before the performance began. One, with a sharp beak of a nose, said to her shorter companion, “I’m glad we’re right down front. I want to see every one of her wrinkles.” It was when I turned to glare that I saw her mean nose. She added, “I shouldn’t say that when she was just so nice to me.” Just? It sounded as if she had been backstage; but if she had just seen Judy Garland face to face, why hadn’t she checked out the wrinkles then?

I had heard her remark. Were people meant to hear? Was she showing off?

In the second row, just to the left of my third-row perch, sat two former New Yorkers. One phrase from each gave away their geographical origin. They looked like tired floozies and were probably respectable Bronx matrons. At mid-show, during the ill-fated Born in a Trunk when Judy tried for a vibrato that didn’t work — it seemed not to work when she tried for what usually came naturally — the one closer to me turned to her companion and said in a loud voice, “Well, she cracked that time, didn’t she?” The trumpet player in the orchestra pit, who was not playing at the moment, leaned over the pit railing towards the two women and mimed drinking from a bottle.

It did not appear to me that Judy Garland was drinking. But there was something fuzzy about her. She acted mildly dazed. She stood and moved as if she had wakened from deep sleep. Her speech was lively enough and distinct.

But the theatrical mystery of the evening, for me, was her sudden appearance. I never saw her enter. Then, there she was, standing left center, for some reason turned sideways to the audience. She wore what I remember as a reddish-brown (maybe wine-colored?) wide-skirted evening gown that looked velvet. If it was meant to conceal extra poundage, it did not. Her face was not quite so full as it had been at the time of her Coconut Grove engagement, but her figure was at least as wide.

I still have my program from this Shrine Auditorium appearance, but I find it is not always assisting my memory. Tt does not show an overture. Was there not one? The first item on the program is “At the Opera,” and that puzzles me. The credits for this specific number show, first, the electrician! (Paul Ely), then boy and girl dancers, next boy and girl singers. I am guessing, these many years later, that this was an introductory extravaganza of arrival which, at the end, brought Judy on in the now explainable gown. This Los Angeles show had originated at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

When the applause for her entrance had finally died she sang I’m in Love With a Wonderful Guy. This was the only time I heard her sing the South Pacific song. I assume that she did not sing this only in Los Angeles but had made it part of her touring show out of New York. (See JUDY NOTE # 1 at the end of this WATCH.)

A long while later in an interview she would talk about being on stage at the Met and feeling that she was giving what she termed “a terrible concert.” On this evening at the Shrine Auditorium I never felt that Judy Garland did any poor singing, much less terrible singing; but this is the only live performance about which I cannot remember being thrilled by anything she sang. There was much that did not work. There was misjudgment in concept; the program seemed ill-conceived. The night’s highlight would be her two encores.

After her opening number she pattered to us about liking to sing a song for the city she was playing. Since no one, she said, had written a song about Los Angeles she would sing what she had sung in Manhattan and she did a fine job of Cole Porter’s mordant I Happen to Like New York.

Gordon Jenkins was in the pit for her that evening and would probably have kicked the trumpet player’s ass if he had seen what I witnessed. She next did four of Jenkins’ songs, having just recorded an LP for Capitol (acted scenes with songs; rather, acted songs with occasional interpolated scenes of dialog). The much-maligned album was called “The Letter.” All the songs and instrumental music were by Jenkins, and it was fun watching him lead her, or follow her, through his own compositions. She had changed from her opening number, and I clearly see her doing the four songs from the album in a sky-to-royal blue taffeta dress with a flaring skirt falling just below her knees.

My friend and driver of the evening Bob would later describe this whole portion of her show as silly schmaltz. My other driver friend, John L. of the earlier Greek Theatre evening, after hearing my 33rpm recording of “The Letter” would say that Jenkins had shown himself undisciplined as to what he expected an American pop singer to be able to execute. The script for the little record drama runs close to the schmaltz friend Bob had claimed; and Judy Garland’s acting co-star John Ireland is as wooden as he is in All the King’s Men and every other movie in which he appeared. But musically knowledgeable John thought that Judy acquitted herself admirably in the difficult vocals.

At the time it was impossible for me to dislike anything the Great Lady sang; but I did genuinely like, and still do, four songs from “The Letter” : Beautiful Trouble, The Worst Kind of Man, The Red Balloon and That’s All There Is, There Isn’t Anymore. There is something else, too, towards the end. It begins, “Come back before the summer is gone . . . ” I don’t know that it is correct to call it a song. What would, what did Jenkins call it? A bridge? A recitative? It’s good, and so is he. I especially admire one line: “Your love has never left its home within my secret heart.”

Judy Garland next proceeded to perform live on stage her Born in a Trunk sequence from her film A Star is Born. Though the Shrine Auditorium was bound to evoke memories of the opening of the film, Born in a Trunk did not work on stage. Pauses between segments were painfully long as blackouts sought to replace film editing. And there was an interesting change. For Swanee she wore a version of the svelte short-skirted black costume she wore for Get Happy in Charles Walters’ Summer Stock. The Judy audience broke into Judy applause when the lights came up and discovered her in the legendary garb. Her audience was willing to suspend the evidence that the costume now revealed Judy’s present weight to the maximum. She stood stock still while delivering Swanee, no doubt having concluded that at this moment of her life, the once-legendary legs look better not in motion. (See JUDY NOTE # 2 at the end of this WATCH for an anecdote concerning the song Born in a Trunk.)

Comedian Alan King and John W. Bubbles, dancer, were on the bill. Together Bubbles and Judy performed Me and My Shadow, reprising Ted Lewis’ version in which Lewis sang while his gestures and movements were mimicked exactly by his small, sexy black sidekick Charles Whittier whom those days and times thought it amusing to nickname Snowball. (See JUDY NOTE # 3 at the end of this WATCH.) Judy Garland did not successfully complete this number. Wearing way-too-tight coat and pants, clearly uncomfortable and sweating, she began the gestures and bodily movements, working as best she could with her partner, but she could not sustain the synchronization. She gave up on all but the singing. She did complete the song.

Then Judy and Alan King executed We’re a Couple of Swells. This left her in her tramp costume for the “Oleo” and Over the Rainbow for which she made dramatic point of not using the microphone. She finished the show with Chicago.

At the end of the show when I connected with my friend, realist and anti-romantic Bob and asked how he felt after his first live Judy Garland performance, he still had not recovered from “The Letter.” He said he had thoroughly enjoyed her last numbers “after she dropped the schmaltz and developed her unique rapport with the audience.”

And I had to admit to myself that during her last quarter hour, right down front with us there (she was in the orchestra pit), she had seemed physically more alert and gave a sense of having gotten her act together.

* * * * * * * * * * *

JUDY NOTE # 1: A recording of the song (from a Bob Hope radio program in 1951) is now available on the four-disc set “Judy Garland, Lost Tracks 1929-1959” (compiled and annotated by Lawrence Schulman, London, JSP Records).

JUDY NOTE # 2: In the fall of 1972 I watched on television the Idaho-Idaho State football game which was played in Pocatello. The pre-game show, brief in those days, began with an appropriate pre-game shot which I cannot recall, but I remember the sound behind it. Judy Garland was singing Born in a Trunk. (The opening words of the song: “I was born in a trunk in the Princess Theatre, in Pocatello, Idaho.”) I was so elated by the originality of this opener that I sent a complimentary letter to ABC Sports, and I received the following generous response:

Please accept my long-delayed thanks for your kind letter of December 27. Mr. Chuck Howard passed it along to me because I produced the telecast of the Idaho-Idaho State game from Pocatello and particularly enjoyed putting together the Judy Garland opening.

Just as an aside, Mr. Jim McKay, the host of ABC’s Wide World of Sports, has written a book (My Wide World by Jim McKay) which is about to be released and in it he makes a brief reference to the opening you liked so much.

Thanks again for taking the time to pass along your compliments. They have been deeply appreciated.

Sincerely,

Doug Wilson

Producer/Director

JUDY NOTE # 3: Polly Miller, formerly of the Ted Lewis Museum in Circleville, OH informed me that over the years Lewis had four different shadows who cavorted with him during this one of his two signature songs. My reference is to the shadow of my memory, the delightful Charles Whittier, whom nationwide movie audiences saw with Abbott and Costello in the film Hold That Ghost.

NEXT Friday POST June 14

Until then,

Enjoy a movie,

Rick